If you have a scar, congratulations! Think of it as a badge of courage and healing. Our expert dermatologists tell how to nurture a new scar to get the best outcome — and, if needed, how to fix an older scar to make it look better.

Almost no one gets through life without a few scars. You can probably trace some milestones with a tour of your own skin: the chicken pox you couldn’t stop scratching when you were 7, the time you fell off your bike, that acne that tormented you in high school or when you had a C-section along with your bundle of joy.

If you’ve been diagnosed with skin cancer and are going in for treatment, good for you. That’s much better than if it stayed undiagnosed and continued to grow. If it’s treated when it’s small, you may not even have a scar. If you need surgery to remove it, you probably will end up with some kind of scar to add to your collection. You may or may not be worried about that. Either way, we want to reassure you that a scar demonstrates the healing power of your own skin. We asked two expert physicians to share their expertise on everything you need to know to be scar-savvy, from wound care to scar repair.

What is a scar, exactly?

A scar is your skin’s natural way of knitting itself back together after it’s been hurt. Healing is a multipart process, and the science behind it is complex. Dermatologic surgeon Mary-Margaret Kober, MD, who practices in the Denver area, helps explain it in simple terms. Wherever there’s been an injury, she says, the first thing that happens is that blood cells called platelets gather together and form a clot to stop the bleeding and seal the wound. Your immune system kicks in and creates inflammation, which helps fight infection and start the healing. Later, cells called fibroblasts make collagen, growth factors and other substances to help mend and rebuild the skin. A few days later, the tissue starts to contract and make a scar. It can take up to a year for a scar to fully heal and reveal its final result. Even when healed, scar tissue is never completely like normal skin. “It’s not quite as strong or as elastic, the color and texture may be different and it doesn’t produce hair, oil or sweat,” Dr. Kober says.

Do skin cancers always need surgery?

Not always. The two most common types of skin cancer are basal cell carcinoma (BCC) and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), the major nonmelanoma skin cancers. Treatment options are based on the size and location of the cancer, and may include topical medications, scraping and burning, freezing, radiation, light-based treatments like lasers and photodynamic therapy, and excision or Mohs surgery.

Excision means the physician surgically removes the tumor with a scalpel, then sends it to a lab for later analysis of the margins. In Mohs surgery, which is recommended for some BCCs and SCCs and requires special training, the Mohs surgeon removes the visible tumor and a very small margin and analyzes the processed tissue in an on-site lab while the patient waits. If any cancer cells remain, they are pinpointed and removed. The surgeon repeats this until there is no evidence of cancer. This technique has a high cure rate and achieves the smallest possible scar, says Dr. Kober, who has extensive training and experience in Mohs surgery.

In rare cases, a BCC or SCC may become advanced and require additional treatment with medications.

Melanomas, which are far less common than BCCs and SCCs, can be more dangerous. Surgery is the most common treatment. Some surgeons are using Mohs surgery successfully on certain cases of melanoma, but this requires additional training. Patients with more advanced melanomas may require additional treatments, such as radiation or medications, including immunotherapies and targeted therapies.

How much do patients worry about scars?

When doctors tell patients they need skin cancer surgery, they hear a wide range of reactions, says Dr. Kober. “I have some patients who say, ‘I don’t care about the scar, Doc. I don’t have a modeling career. Just get the cancer out.’ That’s one extreme.” There are also patients on the other side of the spectrum, she says, who are very concerned about the scar and its cosmetic appearance.

Surgeons do their best to hide scars in the normal folds of the skin, or in smile lines.

Hooman Khorasani, MD, former chief of the Division of Dermatologic & Cosmetic Surgery at Mount Sinai Medical Center in New York City, sees the full gamut of reactions in his private practice on the Upper East Side of Manhattan as well. That includes celebrity patients who know an unsightly scar could hurt their career. Dr. Khorasani, who is quadruple board-certified in dermatology, Mohs surgery, cosmetic surgery and facial cosmetic surgery, spends about 50 percent of his time doing Mohs surgery and says he’s careful to reassure patients as well as manage their expectations. Most cases are BCCs and SCCs. When detected early, they’re almost always curable. “I explain to patients that these are very common skin cancers and that they’re not alone,” he says. “We’re definitely going to take care of it and get rid of the cancer. That’s the most important thing.” He knows the importance of a good cosmetic outcome, too. In fact, he’s done extensive research on minimal scar wound repair.

What should patients expect about the size of a skin cancer surgery wound and the resulting scar?

It’s important to know that the wound that will be created during surgery on a BCC or SCC will be bigger than you might have guessed in advance, says Dr. Khorasani. For one thing, while your skin cancer may have looked like a small red spot when diagnosed, that can be just the tip of the iceberg. There may be extensions, or “roots,” of the cancer that are not visible from the surface that will be discovered during surgery, requiring the removal of more tissue.

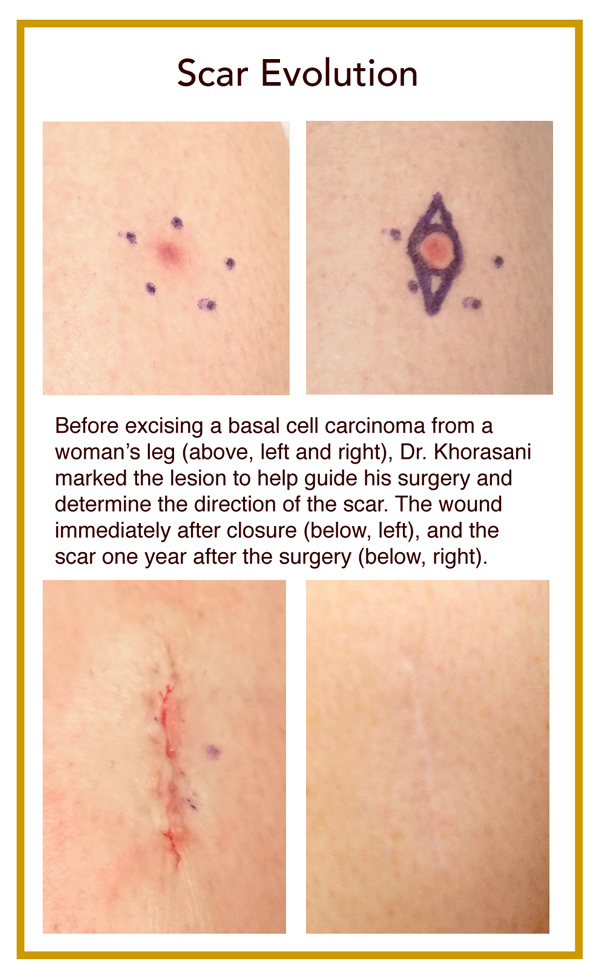

Dr. Kober explains how a circular wound becomes a straight-line scar. “If you try to bring that circle together, the two ends pucker up and become raised,” she says. To correct for that, the surgeon has to remove those little puckers on either end. So before the wound is closed, the surgeon shapes the wound so it looks more like a football than a baseball (doctors call this shape an “ellipse”). “It does lengthen the scar, but it means that the scar lies flat and will look its best.”

The ratio between the diameter of the circle to the length of the ellipse is 1 to 3, Dr. Khorasani explains. Therefore, if you do the math, the length of the scar will be about six times the diameter of the original lesion. “The 10 fellows whom I taught Mohs surgery call this ‘The Khorasani 1 to 6 Scar Rule,’” he says. “They all still use it to educate their patients.”

Public education about this is crucial, he stresses, as a 2020 study in JAMA Dermatology reported that when patients scheduled for Mohs surgery for skin cancer on their face were asked about their expectations before their surgery, more than 80 percent underestimated the length of their resulting scar by about half.

Dr. Kober says that most of the time, Mohs surgeons are able to clear the roots of a tumor by removing just one or two layers of tissue. “But every once in a while, both the patient and I are surprised at how far those roots have traveled. That’s the benefit of Mohs surgery; we can look at 100 percent of the margin and make sure that the skin cancer is out and won’t come back.” She always reassures patients that she will do everything she can to keep the scar as small as possible. “Surgeons also do their best to hide the scar in the normal folds of the skin, or in smile lines,” she says. “The vast majority of the time it heals well and you barely notice it. But if the patient is not completely happy with a scar, there are techniques to improve its appearance.”

Because melanoma is more likely to spread than nonmelanoma skin cancers, surgical guidelines require the doctor to remove a larger safety margin of healthy tissue. Dr. Khorasani says that on average, the wounds from melanoma surgery, and thus the scars, are about twice as large as those from other skin cancers.

What should people know about surgical techniques?

With any surgical procedure, it’s important to look for a doctor who is well-trained, up on the latest techniques and has performed the procedure many times.

When he was teaching medical students about surgical technique and how to handle the tissue, Dr. Khorasani says, “I would tell residents they must treat the epidermis, the top layer of the skin, as if it is the most delicate flower. I would teach them to use a hook to grab the skin rather than a forceps, which can pinch the skin and traumatize that delicate flower of epidermis. I would also tell them that to give the scar an even finish, they have to make sure every edge they’re suturing together is as even as a door on a spaceship.”

Larger skin cancers may need reconstruction using what is called a flap from neighboring skin or sometimes a skin graft from another area of the body.

Are some people just naturally good healers?

Having a good blood supply to the area of the surgery is the number one issue in healing, says Dr. Khorasani. In general, when you’re younger, you have a greater blood supply, so younger people tend to heal well. However, he says he has seen many elderly patients who naturally heal well, too. “I think that just means they have good regenerative machinery. I always ask them what their secret is, especially those over 90 who are super sharp mentally. Some people are just genetically blessed and heal really well — like Wolverine!”

What habits can we learn from good healers?

A healthy diet is very important, says Dr. Khorasani. “And stress hormones can inhibit the wound-healing process, so finding ways to reduce stress, such as meditation, also helps healing.”

Smoking slows down the healing process, and it makes the scars worse, Dr. Kober says. “So please don’t smoke.”

Certain supplements, such as garlic, gingko, vitamin C, fish oil and vitamin E, or medications that thin the blood, such as aspirin, Coumadin or Plavix, can make you more predisposed to bleeding complications that can affect scar healing, says Dr. Kober. It’s important to tell your doctor in advance if you’re taking any of those and get advice on whether you should stop them before or after surgery.

Scar Repair. Left: Dr. Khorasani used a flap of skin from the cheek to cover a wound from Mohs surgery on the nose. Right: The scar after dermabrasion and laser resurfacing.

After surgery, what can patients do for a better scar outcome?

Follow your doctor’s instructions for post-op care. Dr. Kober says that after a surgery, she applies ointment to keep the wound moist and a pressure dressing that stays on for 48 hours. “This helps to immobilize the wound and facilitate the healing process. The pressure also helps to prevent any oozing that might occur after surgery.”

Since Dr. Khorasani now mostly uses internal sutures and rarely uses external sutures, he prefers a special medical glue combined with Steri-Strips (butterfly bandages) for added support. “This makes a kind of external patch that helps protect the wound and simplifies wound care,” he says.

Limit activity so you don’t stretch the wound site. For about two weeks after surgery, Dr. Khorasani says, the wound has only a fraction of its original strength, so any movement can stretch the scar and affect the way it will heal. This can be tricky if your wound is on the back of your hand, for example, or on your lower leg. But if you really want a good outcome, Dr. Khorasani advises, take it easy.

Keep the wound moist with ointment. “Dry wounds heal slower and tend to scar more,” says Dr. Kober. After 48 hours, she recommends that patients remove the dressing, wash the wound gently with plain soap and water and then keep it covered with ointment and a bandage each day until they return to see the doctor, usually in about a week. “We prefer they use a neutral ointment and not an antibiotic ointment because many people develop contact allergies to those,” she explains.

Protect your scar from the sun. New scars tend to darken and discolor when exposed to ultraviolet (UV) light. While you should be protecting your skin from the sun anyway to help prevent future skin cancers, both doctors say that for better scars it is crucial to use sunscreen religiously and keep the area covered if possible. “I advise it for at least the first six months to a year after surgery,” says Dr. Kober.

Protect your scar from the sun for at least the first six months to a year after surgery.

Consider trying a silicone patch or gel. Silicone has been shown to reduce the thickness of some scars, says Dr. Khorasani. After the stitches have been removed, patients can apply an over-the-counter silicone sheet as directed. There’s also a silicone gel with sunscreen in it that dries to form a kind of waterproof shield. Both doctors often recommend silicone for patients who want a minimal scar. “Try the silicone sheets for two months or longer,” says Dr. Kober. “Several silicone gel products go on clear, allowing it to be hidden under makeup. Patients often use these products for three to six months.”

What are the signs of trouble in a healing scar?

Bleeding: Dr. Kober tells patients that if they notice a bit of blood oozing after surgery, “hold firm pressure for 20 minutes on the area — without peeking. If you peek, you release the pressure and have to start the clock over again,” she says. “Most of the time that will solve the problem.” However, for patients who are on blood thinners and don’t clot as well, that may not stop the oozing. “If that’s the case,” Dr. Kober says, “I tell patients to give us a call. We can talk it through, get a sense of how much bleeding there is and, if needed, follow up in the office.”

Infection: Typically, infections are very red, hot and tender, says Dr. Kober. “If it’s a prominent infection, you might see a little yellowy-greenish substance. But sometimes it’s more subtle.” There’s always a little redness associated with the healing process. “But if redness is growing around the wound, or if you have what I describe as pain out of proportion to what you would expect for the normal healing process, call your doctor,” says Dr. Kober. “Most of the time it’s nothing, but it’s always good to put your mind at ease.”

“It’s important for patients to know that infections rarely happen before day five after surgery,” says Dr. Khorasani. “Redness and oozing before day five are often related to allergic reactions.”

If someone doesn’t like a scar, what can be done to improve it?

While many surgeons used to suggest waiting six months or longer to let a scar heal before having treatment to improve the way it looks, Dr. Khorasani says recent studies have shown that early scar treatment can be more beneficial. “It is now becoming more widely accepted that early scars are more receptive to change,” he says. He recommends starting scar treatments six weeks after surgery for cosmetically sensitive areas of the face, for example. Scars that are older can also benefit from some treatments.

Redness: “Redness means blood vessels formed to heal the wound, and they’re still engorged with blood,” says Dr. Khorasani. “We have certain lasers we can treat those vessels with to reduce the redness of a scar.”

Irregularity: “The only thing that really takes care of surface irregularity in a scar is dermabrasion, which is kind of like polishing your skin to even it out,” says Dr. Khorasani. “Don’t worry; it doesn’t hurt.”

Atrophic scars: Some scars are atrophic, which means they are sunken or pitted. “If the depression is too deep, the best option is to do a scar revision and excise the scar. For more shallow depressions, we might also inject fat or a semipermanent filler, such as Bellafill, to help even out atrophic scars,” says Dr. Khorasani.

Texture: The texture of scar tissue is not like the texture of normal skin. “This is because in scar tissue, the collagen fibers are oriented parallel to each other as opposed to normal skin, where collagen fibers are woven together in a basket-weave pattern,” he explains. In order to reverse this, Dr. Khorasani, who completed a yearlong fellowship on this topic, can use a resurfacing laser, like a CO2 laser, to make microscopic wounds. “As these tiny wounds heal, they restore the collagen architecture back to that normal basket-weave pattern.”

Dr. Kober adds, “Particularly on the nose where sebaceous (oil) glands are more prominent, laser resurfacing is a great option. The laser smooths the scar and blends it into the surrounding skin, making it less visible.”

Scars and skin of color: Laser resurfacing with CO2 is not an option for darker skin tones because of the risk of loss of pigmentation, or skin color. Dr. Khorasani says another type of laser, using what is called Pico technology, may be helpful for treatment of scars in skin of color. An effective alternative to lasers, he says, is to use microneedling combined with platelet rich plasma, or PRP. This technique uses microscopic needles to create zones of micro injury within the scar. The growth factors from the platelets help grow new healthy collagen. He also uses microneedling devices that emit radiofrequency heat to stimulate collagen production.

Hypertrophic scars: Certain people may be prone to hypertrophic scars, which are thick and raised, or keloids, where the scar tissue extends outside of the original injury and grows and becomes hard. “We inject steroids to flatten these scars,” says Dr. Kober. “It often takes more than one treatment.” Doctors have also started to add the topical treatment 5-fluourouracil (aka 5-FU) to the steroid mix in order to avoid steroid-induced side effects and thinning of the surrounding tissue, adds Dr. Khorasani.

Combination: Dr. Khorasani says he tries to look at the whole area surrounding a scar before determining the best treatment. “We routinely do a combination treatment,” he says. “For example, if we’re going to be lasering a scar on one cheek, why not consider treating the acne scarring on the other cheek, and make it all even?”

“There is also a synergistic benefit of combining different scar modalities,” he says. “For instance, we routinely combine dermabrasion with CO2 laser resurfacing.” Dermabrasion helps with surface irregularities and removes the top layer of skin to allow the CO2 laser to penetrate a bit deeper into the dermis. And since dermabrasion can cause some bleeding, combining it with CO2 laser treatment helps stop the bleeding.

On the horizon: Dr. Khorasani says that using substances that stimulate collagen production in scars that have resisted other treatments is promising. These include PDO threading (sutures that dissolve and turn into collagen) and injectables like Sculptra.

He also led a study published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology in 2021, which treated forehead scars with injections of botulinum toxin (Botox) versus placebo after Mohs surgery. The patients who received Botox injections into the forehead muscles after the repair of the wound on the forehead had a better overall scar outcome.

Photos courtesy of Hooman Khorasani, MD.

*An earlier version of this article was featured in The Skin Cancer Foundation Journal 2017.

The post Embrace Your Scars appeared first on The Skin Cancer Foundation.