The little spot on my forehead didn’t look like much, but it didn’t feel right to me. Turned out to be squamous cell carcinoma, a more dangerous type of skin cancer than I’d had before.

My favorite childhood memories are of summer days at a crystal-clear lake in northern Minnesota. My best friend Barbie and I would play in and out of the water all day long. While her skin took on a golden glow, mine would turn hot pink and freckly.

Getting Fried

We knew little about the dangers of the sun then. My mom warned me about getting burned. But it wasn’t cool to wear a T-shirt over your cute swimsuit — or a hat. And the tanning lotions we had then were designed to enhance your “deep, dark tan,” not keep you from getting one. Whatever protection they offered washed right off in the water. We were having too much fun to notice. At night, we slathered Noxzema on our burns while we listened to the Beatles. When our skin started to peel, we thought that was cool.

By my teen years, my summers were less about playing in the water and more about the futile pursuit of a beach babe tan. I wanted to look like Farrah Fawcett — or my tall, blonde and tan older sister. My friends and I would “lay out” for hours, and while they would achieve that prom-ready patina, I once ended up in the doctor’s office with second-degree, blistered burns.

I finally started to understand the consequences of inheriting my father’s Scottish-Swedish DNA. I learned my lesson and started to protect myself from the sun. But a lot of damage already had been done.

Skin Cancer at 25

When I was in my mid-20s and living in Dallas, I noticed a scabby spot on my left thigh that never quite seemed to heal. My doctor said it was probably nothing because I was too young to have skin cancer. My instincts told me it wasn’t nothing. He took a small sample of the tissue for a biopsy. Sure enough, it was a basal cell carcinoma (also known as BCC), the most common type of skin cancer. The doctor took care of it with a simple excision and a Band-Aid. I thought that would be the end of it. I was wrong.

My forehead was the next target, and soon it became ground zero for a couple of aggressive BCCs that recurred after excisional surgery.

My forehead was the next target, and soon it became ground zero for a couple of aggressive BCCs that recurred after excisional surgery. That’s when I learned about Mohs surgery, a technique done by a dermatologist who is specially trained. The surgeon removes the visible tumor and a small margin, then examines it under a microscope in an on-site lab while the patient waits. This is different from standard excision, in which the physician closes the wound after removing the tumor, allows the patient to go home and sends the excised tissue to a lab for a pathologist to review.

With Mohs surgery, if any cancer cells remain, the surgeon uses a map to identify where they are and precisely removes them while sparing as much healthy tissue as possible. The doctor repeats this process until no cancer cells are left. Then the Mohs surgeon closes the wound (or, in some cases, a plastic surgeon may reconstruct and close the wound). This technique has the highest cure rate and lowest recurrence rate of any skin cancer treatment, while preserving the maximum amount of normal tissue and allowing the smallest scar possible.

When I moved to New York and became a health writer and editor for magazines, I educated myself about skin cancer and became a bit of an expert on BCC. I learned that while some can be aggressive and recur, they very rarely metastasize or spread to other areas of the body. But they can be “disfiguring,” as the dermatologists say. That means you could end up with a chunk of your face missing and a big ol’ scar. I learned that I was also at risk for more, and other kinds, of skin cancer.

This Spot Seemed Different

By 2012 I had had six BCCs. I often checked my own skin and knew the signs to look for. Then I noticed a spot that seemed different from the others. It was on my scalp, just above the hairline. It seemed kind of itchy or irritated. I didn’t think much of it at first, since I have sensitive skin, and hair products often make my scalp itch. Or I thought it could be a burn from my straightening iron. A few times I felt a little scab come off. I pointed out the spot to my dermatologist, and she thought it was nothing to worry about.

My little spot didn’t look anything like the ugly lesions I’d seen on websites, but it didn’t go away and I was worried. I trusted my instincts and asked David Kriegel, MD, who had done Mohs surgery on a BCC on my arm, to look at it. Dr. Kriegel, then director of the Division of Dermatologic and Mohs Surgery at Mount Sinai Medical Center in New York City, said he listens very closely when patients say they have a gut feeling. “I always tell patients that skin cancers don’t read textbooks,” he says. “People know their own skin.”

A New (Scary) Diagnosis

A biopsy confirmed it. This was a squamous cell carcinoma, or SCC. It’s the second most common form of skin cancer, with more than a million cases each year in the U.S. Dr. Kriegel recommended Mohs surgery. I knew the cure rate for small SCCs like mine is very high with Mohs. But still, the diagnosis scared me, since I also knew that, although it’s uncommon, some large SCCs can spread, or metastasize, and become life-threatening.

After my diagnosis, the strangest coincidence happened. I took a cab home, and the driver shared that his mother had died from squamous cell carcinoma. He was devastated. I felt like I’d been punched in the gut. Really, I thought, people die from this? Yes, while the statistics on nonmelanoma skin cancers are estimates, as many as 15,000 people in the U.S. die from advanced SCC every year.

The driver told me that he was being treated with a topical medication for actinic keratoses (AKs) — precancers that, if left untreated, can develop into SCCs. He got checked out because he promised his mother he would. I promised him I would stay vigilant, too, and use my skills as a journalist to help raise awareness.

My surgery wasn’t fun, but it went fine. (See photos, below.) Since then, I’ve been diagnosed with a few AKs myself, plus several more BCCs and a couple of SCCs, most of which were treated with Mohs surgery. I still love the lakes of northern Minnesota and visit as often as I can. But now I wear protective swim shirts and hats with pride. I monitor my skin regularly, keep notes in my phone about when I first notice a new spot on my skin that is new, changing or unusual, trust my instincts and see my dermatologist at least every six months for a full-body skin exam.

I never imagined that my fun childhood frolics in lakes and pools would lead to skin cancers and a scary surgery on the top of my head.

I decided I wanted to do more to help raise awareness and fight the world’s most common cancer. So, since 2015, I have worked for The Skin Cancer Foundation — a powerful way to fulfill my promise to that cab driver and honor his mother.

My Mohs Surgery, Step by Step

My suspicious spot is above my hairline, right in the middle. Dermatologist David Kriegel, MD, checks it out and decides to do a biopsy.

My suspicious spot is above my hairline, right in the middle. Dermatologist David Kriegel, MD, checks it out and decides to do a biopsy. A close-up of where the lesion has just been removed, to be sent to a lab for a biopsy. It is later diagnosed as a squamous cell carcinoma.

A close-up of where the lesion has just been removed, to be sent to a lab for a biopsy. It is later diagnosed as a squamous cell carcinoma. During Mohs surgery, Dr. Kriegel removes a layer of the squamous cell carcinoma (SCC).

During Mohs surgery, Dr. Kriegel removes a layer of the squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). The SCC is the smaller wound on the left. The larger wound on the right is a basal cell carcinoma (BCC), which the doctor discovered on a previous exam. He agreed to remove both lesions in one Mohs surgery session.

The SCC is the smaller wound on the left. The larger wound on the right is a basal cell carcinoma (BCC), which the doctor discovered on a previous exam. He agreed to remove both lesions in one Mohs surgery session. Bandaged and waiting between rounds of surgery while the lab work is done, I’m a little worried about my hair, but I feel OK! The SCC takes two rounds of surgery. The larger BCC needs three rounds of surgery.

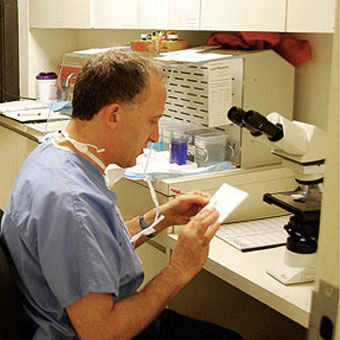

Bandaged and waiting between rounds of surgery while the lab work is done, I’m a little worried about my hair, but I feel OK! The SCC takes two rounds of surgery. The larger BCC needs three rounds of surgery. Dr. Kriegel examines a section of my SCC tumor under the microscope.

Dr. Kriegel examines a section of my SCC tumor under the microscope. Dr. Kriegel draws a map of where cancer cells remain on my scalp to guide him in the next round of surgery. The whole procedure ends up taking about six hours.

Dr. Kriegel draws a map of where cancer cells remain on my scalp to guide him in the next round of surgery. The whole procedure ends up taking about six hours. When both tumors are given the all-clear by Dr. Kriegel, it’s time to close the wounds. To save as much hair and scalp as possible, plastic surgeon Robert M. Schwarcz, MD, who often works with Dr. Kriegel, finishes it up.

When both tumors are given the all-clear by Dr. Kriegel, it’s time to close the wounds. To save as much hair and scalp as possible, plastic surgeon Robert M. Schwarcz, MD, who often works with Dr. Kriegel, finishes it up. Headbands and scarves help to hide the wounds healing (and greasy hair from ointment!)

Headbands and scarves help to hide the wounds healing (and greasy hair from ointment!) Selfie of my wounds healing. I have a little post-surgery bleeding, which anecdotally, doctors say, seems more common in redheads. It hasn’t been proven why that might be.

Selfie of my wounds healing. I have a little post-surgery bleeding, which anecdotally, doctors say, seems more common in redheads. It hasn’t been proven why that might be. Now: I have several scars on my forehead and scalp. They’re not bad, but still, thank God for bangs!

Now: I have several scars on my forehead and scalp. They’re not bad, but still, thank God for bangs!

Julie Bain is senior director of science & education at The Skin Cancer Foundation.

The post A Hole in My Head appeared first on The Skin Cancer Foundation.